Understanding Fire Behavior for Today's Firefighters

Fire behavior is one of the most critical areas of knowledge for any firefighter. It directly impacts decisions on the fireground and is key to ensuring the safety of personnel and the effectiveness of tactical operations. At its core, fire requires three essential components to exist—heat, fuel, and oxygen—collectively known as the fire triangle. However, to truly understand fire behavior, we must go a step further and include the chemical chain reaction, forming what is called the fire tetrahedron. This reaction sustains combustion, and disrupting any one of these elements will lead to fire extinguishment.

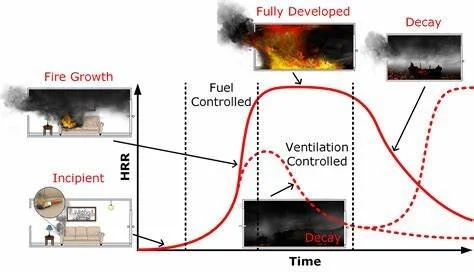

Fires progress through a predictable series of stages: the incipient stage (initial ignition with minimal visible signs), the growth stage (where the fire begins to intensify and spread), the fully developed stage (maximum heat release and flame spread), and the decay stage (where fuel and oxygen begin to run out). Each stage presents unique threats and demands a specific tactical approach. Recognizing and anticipating these transitions is crucial for safe entry, ventilation timing, and suppression tactics.

Among the most dangerous phenomena firefighters may encounter are flashover, rollover, and backdraft. Flashover is the near-simultaneous ignition of all combustibles in a space due to high temperatures and thermal radiation. Rollover is the ignition of hot gases that have risen to the ceiling, often a precursor to flashover. Backdraft is an explosive event caused by the sudden reintroduction of oxygen into a superheated, oxygen-deprived environment. All three present extreme danger and require situational awareness and early recognition.

Smoke itself is an invaluable indicator of fire conditions. Its color, velocity, volume, and density can provide early clues to fire location, intensity, fuel type, and potential hazards. Light-colored smoke may indicate early-stage fires or clean-burning fuels, while dark, turbulent, fast-moving smoke suggests high heat and dangerous fire growth. Reading smoke is an essential skill that gives firefighters an edge in identifying flashover conditions, collapse zones, and points of safe or unsafe entry.

Fire spreads in three primary ways: conduction (heat traveling through solid materials like metal beams), convection (heat and gases moving upward through open spaces and ventilation paths), and radiation (heat traveling through space and igniting surfaces at a distance). Understanding these modes of fire travel is essential when assessing fire spread potential, protecting exposures, and predicting the fire’s next move.

In today’s fire environment—fueled by synthetic materials and affected by lightweight construction—the speed and severity of fire growth are greater than ever before. This reality demands not just physical readiness but also a mental and strategic understanding of how fire behaves. Firefighters must approach each incident with a trained eye, constantly evaluating smoke conditions, building construction, ventilation profiles, and environmental factors like wind.

Ultimately, fire behavior is not just a theoretical subject—it’s a life-or-death factor on every scene. By studying it, drilling it, and applying it, we increase our operational effectiveness, protect our crews, and uphold our mission to save lives and property. The fireground is dynamic and unforgiving, but through knowledge, preparation, and observation, we can meet its challenges head-on.

Until next time - work hard, stay safe & live inspired.