In the fire service, this principle emphasizes that by tracking and evaluating specific metrics, departments can improve performance, increase safety, allocate resources efficiently, and enhance community service. But it also comes with the caveat: measure the wrong thing, and you may manage the wrong priorities.

Speaking of measurements, let's briefly discuss NFPA 1710 and its impact on setting benchmarks for response times. NFPA 1710 is a standard developed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) that sets performance benchmarks for response times in career fire departments. It defines specific timeframes for each phase of emergency response—from the initial call receipt to the stabilization of the incident. The main objective of the standard is to promote effective and timely emergency response to protect public safety, providing clear guidelines on staffing levels and operational timelines.

Factors that may affect response time are geographic layout, traffic conditions, staffing levels, equipment readiness and call volume.

The 2020 edition of NFPA 1710 introduced key updates to reflect the evolving demands on modern fire departments. One major change was an increased emphasis on emergency medical services (EMS), acknowledging the growing number of medical calls. The standard now requires EMS units to arrive within 8 minutes, 90% of the time, underscoring the critical need for timely medical response.

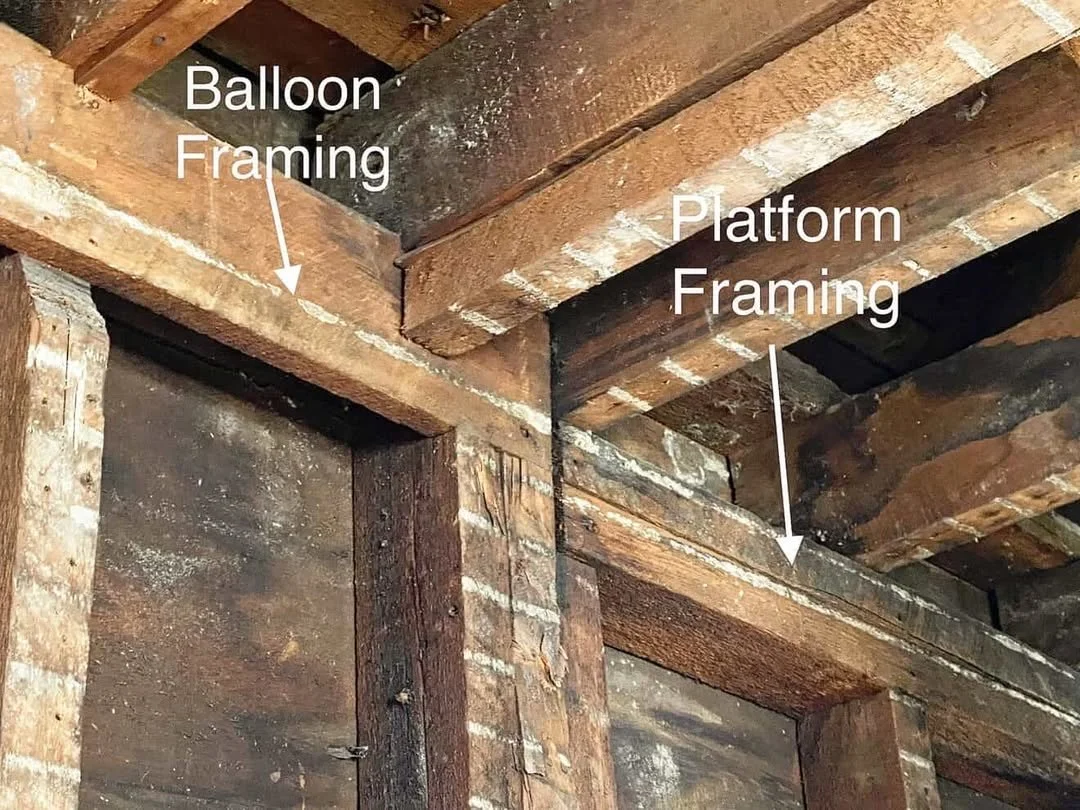

Another significant revision includes detailed response benchmarks based on occupancy types—such as high-rise buildings, single-family homes, and open-air strip malls—ensuring departments tailor resource deployment to specific incident scenarios with greater scalability and adaptability.

The updated standard also expanded crew size recommendations, particularly for high-risk or complex incidents, to improve firefighter safety and operational efficiency. In addition, it addressed emerging technologies, encouraging the adoption of tools like digital communication systems and real-time tracking to enhance coordination and situational awareness.

Overall, the 2020 updates strengthen NFPA 1710 as a comprehensive, modern framework designed to support effective emergency response and meet public safety expectations.

Below are key areas not specifically impacted by NFPA 1710 but areas of management that departments can identify to improve performance, increase safety, allocate resources efficiently, and enhance community service.

Response Times

Measured: Time from dispatch to arrival on scene.

Managed: Departments may adjust station locations, shift staffing, or invest in traffic preemption systems to reduce response times.

Example: A department notices longer response times in a growing suburban area. By tracking this consistently, leadership advocates for a new station in that zone to improve coverage.

Call Processing Time: No more than 64 seconds, 95% of the time.

Turnout Time: Firefighters should be suited and in their apparatus within 80 seconds for fire responses and 60 seconds for EMS calls.

Travel Time: First responders should arrive on the scene within 240 seconds (4 minutes) for fire suppression and EMS incidents, 90% of the time.

Call Volume by Type and Location

Measured: Number of EMS, fire, hazmat, and false alarm calls per area.

Managed: Resources (staffing, apparatus, training) are tailored to meet actual demand.

Example: If 80% of calls are EMS-related, the department may prioritize EMT training and consider deploying smaller, faster response vehicles for medical calls.

Firefighter Injuries and Near Misses

Measured: Frequency, type, and causes of injuries or close calls.

Managed: Safety protocols, PPE standards, and training are improved based on trends.

Example: A spike in ladder-related injuries leads to updated SOPs and targeted training sessions.

Training Hours and Competency

Measured: Training hours completed per firefighter, and performance on practical assessments.

Managed: Ensures compliance with standards (e.g., NFPA), identifies gaps, and supports skill development.

Example: If quarterly evaluations show low performance in RIT (Rapid Intervention Team) drills, the department schedules additional hands-on and classroom training to assist in improving RIT performance.

Fire Prevention Activities

Measured: Number of inspections, public education sessions, or code violations found.

Managed: Prevention programs and staffing are adjusted to reduce fire risk.

Example: Data shows increased violations in commercial kitchens, prompting a targeted inspection blitz and education campaign.

Community Risk Reduction (CRR)

Measured: Data on fire incidents, demographics, and high-risk properties.

Managed: Outreach and mitigation strategies are focused on vulnerable populations or high-risk buildings.

Example: Elderly residents in a mobile home park experience frequent cooking fires. The department installs stovetop fire suppressors and offers safety classes.

The Caution: Measure What Matters

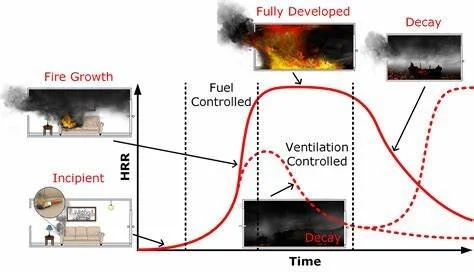

If a department only measures response time, it might push crews to speed at the cost of safety. If it only tracks number of calls, it may ignore quality of service or fire prevention success. That’s why contextual, balanced measurement is key.

In the fire service, measuring the right things leads to better management—more effective responses, safer firefighters, better-trained personnel, and stronger community outcomes. But success depends not just on measuring, but on measuring what truly matters to mission effectiveness and public safety.

Until next time - work hard, stay safe & live inspired.